Midwives and the Church

The best source we have for identifying early modern midwives are the testimonials that practitioners submitted when they sought a midwifery license from the Church of England. In most cases these testimonials included two statements: one from a local clergyman or the parish churchwardens stating that the applicant was of good character and a member of the Church of England, and another from local women that she was skilled at delivering children. The paradox is immediately evident – in order to receive a license to practice midwifery, a woman had to have experience as a midwife. In some cases a midwife would train an assistant who, after an unofficial apprenticeship, would become a midwife in her own right. A formal system for training deputy midwives was established in London, and Bridget Hodgson remembered her deputy in her will, but aside fro London we do not know how common this practice might have been.

The best source we have for identifying early modern midwives are the testimonials that practitioners submitted when they sought a midwifery license from the Church of England. In most cases these testimonials included two statements: one from a local clergyman or the parish churchwardens stating that the applicant was of good character and a member of the Church of England, and another from local women that she was skilled at delivering children. The paradox is immediately evident – in order to receive a license to practice midwifery, a woman had to have experience as a midwife. In some cases a midwife would train an assistant who, after an unofficial apprenticeship, would become a midwife in her own right. A formal system for training deputy midwives was established in London, and Bridget Hodgson remembered her deputy in her will, but aside fro London we do not know how common this practice might have been.

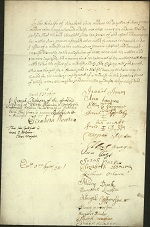

When we look at the midwife testimonials, we see that some women had a great deal of experience before they applied for a license. Helen Taylor of Pontefract claimed seven years’ experience, and according to her nomination Alice Constable was, “a practiced and experienced midwife, as not only we whose hands are hereunto subscribed but hundreds more good women within this parish (to their benefit) can attest.” Even if we allow for a measure of exaggeration, it seems clear that Constable had been a working midwife for some time before she applied for a license. But why would a woman such as Alice Constable risk a citation from the Church rather than simply get the license?

When we look at the midwife testimonials, we see that some women had a great deal of experience before they applied for a license. Helen Taylor of Pontefract claimed seven years’ experience, and according to her nomination Alice Constable was, “a practiced and experienced midwife, as not only we whose hands are hereunto subscribed but hundreds more good women within this parish (to their benefit) can attest.” Even if we allow for a measure of exaggeration, it seems clear that Constable had been a working midwife for some time before she applied for a license. But why would a woman such as Alice Constable risk a citation from the Church rather than simply get the license?